Commentary: Patients are dying unnecessarily while waiting for organ donors

Organ donation isn't just about one life - it's about potentially saving nine, say NUS Medicine’s Professor Julian Savulescu and Dr Sumytra Menon.

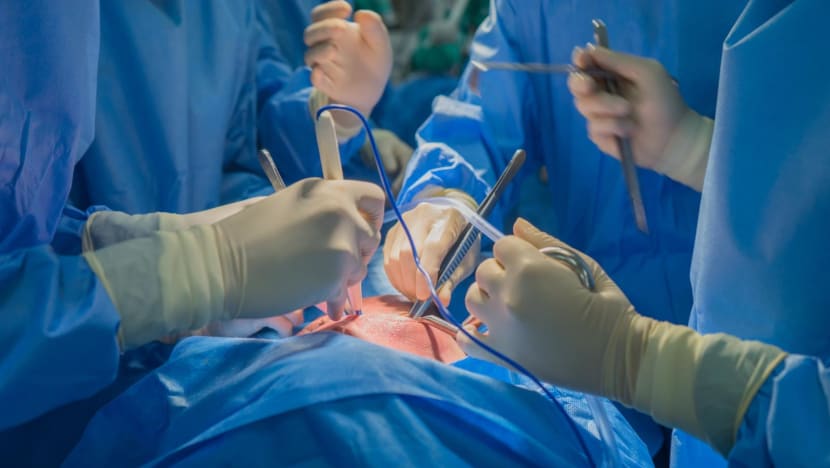

File photo. After death, a person’s organs and tissues could save or significantly improve at least nine other lives through transplant. (Photo: iStock/Shuttermon)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: There are more than 500 people on the waiting list for an organ transplant in Singapore. Some of them might die before an organ is available, while others might become ineligible due to deteriorating health.

Take the case of Boon Heng, a 15-year-old boy fighting for his life against end-stage liver disease. The boy, who suffers from a rare condition called primary sclerosing cholangitis, has been searching for a donor for more than a year. Despite some media coverage, and personally handing out flyers on the streets to appeal for donors, a compatible donor has not yet been found.

The topic of organ donation has been in the spotlight recently, following news reports of the tragic case of 14-year-old Isaac Loo who collapsed during a 2.4km run in school and fell into a coma. His mother, Fiona, initially agreed to donate his organs, then changed her mind.

‘“I couldn’t bear to do it. I thought Isaac had already suffered for three weeks, for so long. I could not make the decision again to cut up his body,” she told local media.

However, when told of the hundreds of people on the organ transplant wait list, she decided to donate. One can only admire her bravery and moral fortitude. Isaac’s organs were reportedly donated to at least three patients.

WHEN FAMILY WISHES LEAD THE WAY

The decision to donate organs can have emotional costs, especially when it is a parent choosing to donate a child’s organs.

Singapore has adopted two key strategies to increase organ donation. First, it has an opt-out system where people are presumed to donate unless they explicitly object. Only about 3 per cent object.

Second, it deprioritises those who choose to opt out if they do eventually require an organ. This is based on principles of solidarity and reciprocity for those who choose to contribute.

Despite these efforts, Singapore has a low rate of deceased organ donation - 3.56 people per million population donated in 2022, according to the International Registry in Organ Donation and Transplantation. Globally the rate is 6.84. In Spain, which has the highest donation rates in the world, the rate is 47.02.

So why the low rate in Singapore? A CNA article featuring interviews with organ transplant surgeons last month revealed that resistance from family members is an obstacle.

Other reports have suggested that families reluctant to donate the organs of their loved ones either choose to keep the patient out of the ICU or have their life support removed before brain death can be ascertained. While they have no legal or moral right to do this, doctors typically respect their wishes, not wishing to impose emotional stress on grieving relatives.

SAVING NINE LIVES

After death, a person’s organs and tissues could save or significantly improve at least nine other lives through transplant. This means that for each person who does not donate, up to nine other people could die or significantly suffer.

A local study published in 2017 in the Frontiers in Public Health journal concluded that knowledge gaps, for example not knowing that brain death was irreversible, cultural and religious considerations, and the emotional impact of the relatives’ death are the reasons for the low organ donation rates in Singapore.

The study showed that 46.3 per cent of respondents thought that brain death was reversible and only 11.5 per cent of respondents realised that brain death certification involved a stringent process. This shows that Singaporeans have significant misconceptions about brain death.

The authors of the study recommended investment in public education, enhancing transplant provisions and supporting families through the process. We agree these are the things Singapore could do to increase its organ donation rate.

First, there is education and psychological support. Spain has the highest organ donation rate in the world. This is achieved by a combination of opt-out and significant family support, where coordinators, who have been intensively trained to communicate effectively with families, discuss whether the patient would have wanted to donate their organs. They respect the family’s decision if they refuse.

Singapore could consider the same approach. However, this has financial and other resource costs - the money that goes into support could be used for other medical care.

Second, there are incentives. Financial incentives such as covering funeral costs or a subsidy to offset the family’s medical care costs might help ease some barriers to organ donation.

Third, there are disincentives. Singapore already employs one disincentive: Lowering your priority for an organ if you opt out of donation. Some have proposed extending this to family members who object, so that they would receive lower priority if they need a transplant. Although this takes into consideration fairness and reciprocity in organ allocation, it also raises ethical issues. Should someone's access to potential life-saving treatment in the future be influenced by a decision they made during an already difficult time?

The narrative around donation could be shifted to emphasise its importance as a moral obligation in society - if people have been given the chance to opt out and have not, then families should accept this as the person’s decision to donate.

If a persuasive case is made that donation is in our best interests as a nation, perhaps our donation rates may improve.

Finally, there are fines and other legal forms of coercion, such as legally requiring doctors to take organs from people who have explicitly consented, regardless of family wishes, but it is hard to see how this could be acceptable in Singapore.

While cultural views (such as burying or burning the body intact) and religious views (although all the mainstream religions in Singapore have no objection to deceased organ donation) should be respected, it is hard to fathom losing these literally life-saving resources.

What should Singapore do? Something. It’s pretty clear we need to increase our pool of organ donors. If not for Boon Heng, then for the other hundreds of patients on the waiting list.

Professor Julian Savulescu is Director, Centre for Biomedical Ethics (CBmE) at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. Dr Sumytra Menon is Deputy Director of CBmE.