Fight or Flee: Tuvalu’s residents prepare for mass displacement as nation forecast to be among first to disappear due to climate change

If your country no longer physically exists, what does that make you? It’s an existential question residents of one of the smallest and most climate-vulnerable countries on the planet are contemplating. This is the first of a three-part series by CNA on how Pacific island-nations are fighting climate change, and the lessons they offer.

Tuvalu's coastline is highly vulnerable to rising sea levels. (Photo: CNA/Jack Board)

FUNAFUTI, Tuvalu: As the ocean grew dark and violent, lashing at the exposed shoreline, Ms Gitty Yee grabbed her camera and ran out towards the maelstrom.

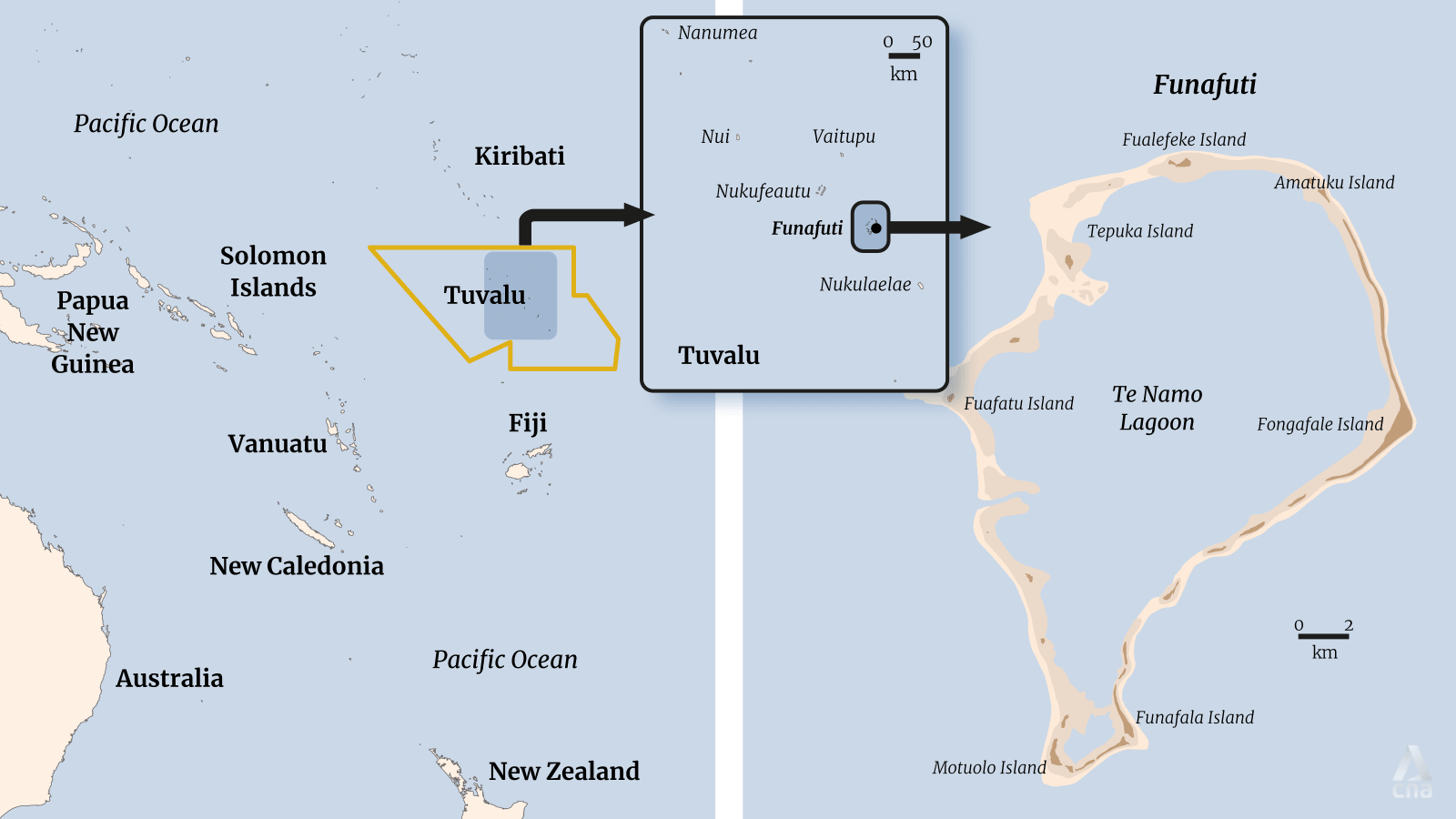

A powerful storm had arrived in Tuvalu, punctuated by a king tide. Powerful waves rose to engulf the flanks of the narrow main island of Fongafale, leaving trails of debris on the main two-lane road that runs from toe to tip.

“It was actually the worst one I've ever seen,” the 25-year-old amateur photographer recounted of the calamity back in February.

“It really damaged a lot of homes. It destroyed some seawalls and the water was up to our knees,” she said.

Amid the turbulence, the Tuvalu native turned her gaze - and her lens - towards local children coming out to swim, delighting in the swell and oblivious to the apparent dangers of an angry Pacific Ocean.

It will be like this every time the tide rises, she explained.

Its peril on the geographical margins has led it to try and become a powerful voice at the centre of global climate negotiations - a thorn in the side of heavy polluters. At the same time, it is reckoning with a future where the nation may only exist in the metaverse.

Under a high global emissions scenario - assuming that world greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase at current rates and considering Tuvalu’s existing infrastructure - 95 per cent of capital city Funafuti is expected to be flooded on a daily basis by the end of the century. It would be uninhabitable a long time before then - possibly as early as 2050.

Given the scientific projections, Tuvalu has become the poster child for sea level rise inundation.

For Tuvalu’s climate change minister, Maina Talia, there is strong symbolism in the joy of the country’s young residents regardless of the existential threat that hangs over their fates.

“Despite the fact that we still have that concept of fear in the face of climate change, at the same time, you will see the kids enjoying the sea,” he said.

“They are playing around the shorelines and they are enjoying the high tide, knowing very well it's devastating our lives and who we are as people. But yet, we can do nothing,” he said.

The nation has become a curiosity, now increasingly attracting researchers and writers to understand the unfolding phenomenon. It is a morbid examination of what it means for an entire country to disappear off the face of the map.

Even some locals are leaning into the narrative. At one of the guesthouses in Funafuti, t-shirts hang for sale behind reception. “Tuvalu, frontline to climate change" and “Tuvalu, where climate change is a reality” adorn their fronts.

But for those deep in the fight, the situation is more than a slogan. It is a matter of saving a place, a culture and a people.

THE LIBERTY TO LEAVE

It was just a few years ago that Tuvalu’s then-foreign minister, Simon Kofe, stood at a lectern, knee-deep in water at the northern tip of Fongafale, and made an impassioned address about the impacts of climate change on his country and the wider world.

“We cannot wait for speeches while the sea around us is rising all the time,” he said, ahead of global climate talks at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow in 2022. “We are sinking, but so is everyone else.”

Not much has altered the country’s prospects since then. Tuvalu is still living on the edge, trying to stay afloat in the face of oblivion.

Seawater regularly gushes into people’s homes and businesses, cloistered between the open ocean and a lagoon. In parts, the main island - and in effect the country - is just metres wide - and from end to end, Fongafale is just 12km in length.

The government has taken proactive measures to protect the sovereignty of the nation and ensure its continuity going forward, regardless of what unfolds on the climate front.

In September last year, the country’s constitution was amended to state that Tuvalu’s statehood would remain in perpetuity, regardless of whether its physical territory was lost.

It was a move that theoretically shored up Tuvalu’s existence as a nation, but raised another discussion about a worst-case scenario - moving the entire country to a new place.

For now, the current government is adamant that relocation is not on the agenda.

“Our government continues to insist that migration is a definite no. But it's a matter of choice for our people. People have liberty to leave if they are willing to,” Dr Talia said.

He explained, however, that the administration would help facilitate the processes and pathways for Tuvaluans to consider their future options, while prioritising safeguarding their home.

“Our role as the government is to ensure that we keep Tuvalu afloat because if we are to migrate to other parts of the world, one day, my kids will ask me, where is Tuvalu? Where are we from? And Tuvalu has already disappeared from the face of the earth,” he said.

The ink is still drying on a security partnership arrangement with Australia that could soon see hundreds of Tuvaluans moving overseas every year.

The Falepili Union treaty was agreed in November 2023 between the two respective governments to facilitate 280 long-term visas annually for Tuvaluans, framed as a “special human mobility pathway” for individuals and families to live, work and study in Australia.

For a country with a total population of about 12,000 people, it’s a “big number”, said Mr Paulson Panapa, Tuvalu’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, Labour & Trade.

“These are important opportunities for people. It's purely optional. It's up to the person if they want to go and live in Australia,” said Mr Panapa.

“But I think as a government, it's our duty to provide pathways so that our people can start a new life in Australia. It doesn’t mean it’s not good here, but employment opportunities are difficult.”

He said he hopes that young people gaining a foreign education can help Tuvalu develop further in the years to come. There is an expectation that the visa opportunity does not come bound with a one-way ticket.

The initiative is part of a broader package with Australia that also focuses on climate cooperation, underpinned by the Tuvalu people’s desire to remain living on their own territory.

“The Parties commit to work together to help the citizens of Tuvalu to stay in their homes with safety and dignity,” the treaty reads.

It also recognised “the special and unique circumstances faced by Tuvalu and that climate change is Tuvalu's greatest national security concern”.

Intertwined with climate-related support, including millions of dollars for Tuvalu to expand its landmass through reclamation by 6 per cent, there are security implications too.

Namely, it means Canberra must agree to any defence pact Tuvalu wants to sign with another nation, and in return Australia has vowed to militarily defend its Pacific neighbour.

Mr Panapa told CNA that although the treaty has been signed, details are still being negotiated before it becomes operational.

It is an early example of climate migration, a growing area of consideration globally.

Beyond these fragile shores, hundreds of millions of people face a similar threat of coastal flooding in the decades ahead. A 2021 World Bank report found more than 200 million people are likely to migrate by 2050 due to slow-onset climate change impacts.

International and regional courts are in the process of clarifying existing legal obligations to address the issue.

Climate director at the International Refugee Assistance Project Ama Francis said governments from high-emitting countries have a moral responsibility and obligation to provide migration assistance to climate-impacted people, due to their historical emissions fuelling the displacement that is currently occurring.

Australia is the world's 14th highest emitter, contributing just over 1 per cent of global emissions.

“The agreement between Australia and Tuvalu goes to show that governments are starting to recognise that addressing migration is an important part of our response to climate change. Proactive agreements like these are important because planning for migration makes for much better outcomes,” they said.

“People will be on the move regardless of what governments do. What creating legal and accessible pathways for climate-displaced people does is give people dignified options and enables them to make their own decisions to ensure cultural survival.”

MEMORIES IN THE METAVERSE

As a measure to timestamp Tuvalu and its landmarks and features before potential catastrophe strikes, the government has also been eyeing what solutions technology can offer.

In 2022, Mr Kofe proposed the country recreate itself digitally. That would mean a digital twin existing in the metaverse, aimed at preserving Tuvalu’s culture, heritage and atolls.

Singapore has already created something similar for itself, but “Virtual Singapore” exists not as a memorial or a time capsule but as a working tool to develop and test urban solutions and technologies.

“Tuvalu could be the first country in the world to exist solely in cyberspace – but if global warming continues unchecked, it won’t be the last,” Mr Kofe said at the time.

While the concept has not progressed much since, the idea sparked fierce debate - about the limits and costs of technology and the merits of preserving culture in the virtual world.

“There is some validity and credibility to that (idea). It's all about providing alternatives and how we can ensure that we have continuity,” Dr Talia said.

“(But) protecting our shorelines and elevating the land, I think will be the most practicable thing to do, and to engage with. And I'm sure that the support from the donor communities is there to ensure that we will continue to be in our islands,” he said.

For Mr Richard Gorkrun, the executive director of the Tuvalu Climate Action Network, focusing on the metaverse is akin to giving up on the physical world.

“We know there are some aspects that may be beneficial to preserve our culture and the appearance of the current landscape in a digital world for the next generation to see,” he said.

“But that doesn't really fully capture the essence of cultural Tuvaluan lifestyle which intertwines with the physical land that we are living on now. It's totally like we are giving up on development and the fight to maintain our country.”

Tuvalu is a deeply traditional nation that fuses age-old beliefs with devout Christianity. At 6.45pm every day for example, the entire country falls silent - traffic must stop - to respect a nationwide period of quiet devotion.

Elder Kalisi Sogibalu fears the erosion of the values, languages and customs that make this place unique and special.

Yet, he also sees first hand what climate change is doing to his home. Every day the 66-year-old steers his small boat from Funafuti to a smaller southern atoll, where his family has land, a farm and a simple house.

The damage unfolding is serious and he is pragmatic about what that means for the future.

“We might be the first refugees somewhere else, in big countries. But let us hope it doesn't happen,” he said.

“The problem is whether another country will accept our culture. But we will carry it with us, as we were born in it and we grew up in it. And it's really hard to let it go just like that.”

TUVALU’S REFUGE

In the meantime, young Tuvaluans are now entrapped in a dilemma. They are being asked to decide between fighting on home soil or forsaking it altogether.

Like many of her peers, Ms Yee is aware of the doomsday narrative that has engulfed her nation.

The draw to greater work and education opportunities overseas is real. She is resisting for now but has friends who are ready to move.

“I think that most of my friends who are planning to leave Tuvalu, they just want to have a better future. I don't think they see a bright future for them here in Tuvalu,” she said.

“But growing up in Tuvalu, this place is like home. So from my own perspective, I wouldn't want to leave even though we're being told a lot of things about Tuvalu, that it’s going to go underwater. And the thing is, we're just trying to adapt to something that we didn't create in the first place, which is sad.”

For Ms Yee, her camera has become a tool to capture the spirit of her homeland. And while she is intent on documenting climate change-induced damage on the islands, showcasing regular life is also important.

She hopes it can show the world that climate-affected people are not ready to be defined as victims.

“There’s so much more to Tuvalu than just climate change and being vulnerable to climate change,” she said.

“There's our traditions and cultures, there's our way of living and there's our local food. There are our beautiful landscapes and especially, there’s the sunset.”

Dusk brings about ritual across Funafuti on a daily basis. As the scorching heat of the day dissipates with the light, families emerge to swim in the shallows - literally metres from their shoreline homes.

On the island’s international runway - used normally just once a day for the flight in and out of Fiji - crowds gather to play volleyball or rugby. Children ride their bicycles and teens stroll along the length of the tarmac, in lieu of empty space elsewhere on the atoll. Slowly, striking colour ripples along the horizon and bursts high into the sky as the sun dips out of sight.

The irony of capturing the best view of the sunset these days is that it is from the vantage point of a large patch of reclaimed land.

Part of the L-TAP or “Te Lafiga o Tuvalu” (Tuvalu’s Refuge) Project, the seven-hectare landmark development cost millions of dollars and was mostly funded by the United Nations (UN)’s Green Climate Fund.

In the future, residents in areas facing serious inundation are earmarked to relocate here. There remain stumbling blocks to that happening for now, including disputes about the permanence of such a move and around land ownership.

Even more reclamation plans are in the pipeline. Eventually, the size of Funafuti could almost be doubled by filling in land on the lagoon side of the capital.

The L-TAP vision involves building “3.6 sq km of raised, safe land with staged relocation of people and infrastructure over time”. It also includes plans to improve access to drinking water, renewable energy sources, food security and storm-resistant infrastructure.

Whether such plans can be realised is contingent on unlocking vast amounts of global climate funds, contributed by other nations as part of climate loss and damage or adaptation mechanisms. The estimated cost of L-TAP is more than US$1 billion, while Tuvalu’s GDP in 2022 was just US$60 million.

“I understand it's a very expensive exercise to undertake. But what else can we do? It's a life and death issue for us,” Dr Talia said.

At COP28 in Dubai last year, delegates agreed to formally establish a loss and damage fund to support vulnerable countries. However, injecting the necessary money into that fund and then distributing it in a timely fashion remains an ongoing challenge.

Young people in Tuvalu are attempting to take grip of the efforts to draw attention and funding to the Pacific. “It’s an extreme issue for us,” said Mr Talua Nivaga, a youth climate activist leader in Tuvalu and the founder of an environmental youth-led organisation.

“We are working collaboratively and collectively to ensure that we will survive and we will not drown,” he said.

Mr Nivaga’s ongoing work is aimed at elevating local people’s understanding of climate finance mechanisms and ways and opportunities to access them. He is clear that the time is over for proving to the world what is happening in Tuvalu.

“The world is fully aware that we are affected. We are talking about lives, we are talking about children, we are talking about the most vulnerable people that are facing the consequences of the actions of others,” he said.

He is in step with his climate change minister, the man who will lead Tuvalu's advocacy at global negotiations for the foreseeable future.

Dr Talia, new to the climate portfolio following a national election earlier this year, said not to expect theatrics from him on the world stage - no videos standing in the ocean.

“We should not romanticise climate change. We're talking about the survival of people not just in Tuvalu, but those who are unfortunate to be in low lying atolls,” he said.

“The polluting countries should come to terms with this. And we should continue to hold them accountable for their actions.”